“Of all the communities in antiquity, it was Rome –through meticulously studied iconographies– that made the most intensive use of the coin as an instrument of communication at the service of those in power”. It is by means of this presentation letter that we enter the exhibition “Coins in the time of Augustus”, available until the end of the summer in the Museu Nacional Arqueològic de Tarragona.

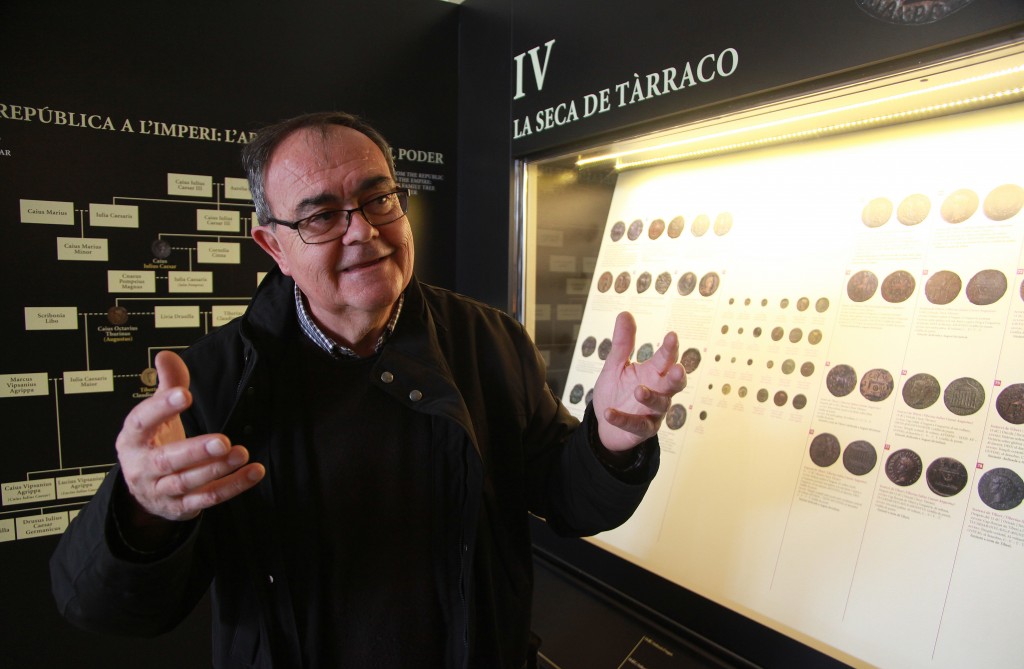

The showing was initially scheduled for 2014, the moment the city commemorated the 2nd millennium of the death of the emperor. However, and due to conjectural reasons –which have nothing to do with how prices change in the different international trading floors–, it was never opened, and so it was finally presented in the late 2015. Today though, we’re happy it took that long, as it has been well worth it the waiting. To start with, and as Francesc Tarrats, the MNAT director explains, the exhibition covers one of the museum’s deficiencies, the question of numismatics. This is the reason why, and despite the showing being temporary, the Museu decided to refurbish the area of the building that today homes the exhibition, so that it could become a more attractive space and reinforce the resulting museum narrative thread.

“Coins in the time of Augustus” is a selective showing and it only presents 79 items, property of local and Catalan collectors, for the most part. However, this numismatic exhibition has great value because it represents the story of Augustus’ vital journey, from the year 63 BC, when he was born, until 14 AD, when he died. “Coins in the time of Augustus”, says Tarrats, gathers “a representative selection of the coins that were current in the integrated territories of the Roman world in that period. A selection”, he adds, “that, in the particular case of Tarraco, becomes exhaustive, as it gathers, for the first time, the entire series of the coins mint in the city and, for the most part, after the memory of Augustus and the worship of his divinity, process on which Tarragona became pioneer”.

In this context, the showing is structured in four main fields: the first goes from the birth of Augustus (63 BC) to the death of Caesar (44 BC); the second, from the death of Caesar to the Empire of Augustus (27 BC); the third tells us about the time of the Empire of Augustus (27BC-14AD), plus his death and legacy; and as for the fourth and last, it focuses on the mint of Tarraco, which was the actual house or workshop where coins were made in the city, under the authorisation of Rome. In the showing, you will get to admire all the coins made during the time of Augustus and Tiberius.

The showing starts with the issuance of the first coins made during the birth, childhood and training of Augustus, until the death of Julius Caesar. This is the pre-imperial and late-republican time, when the great Italian families were in control of the issue and message, under the supervision of the Senate. In this period though, coins don’t illustrate royal characters, but iconography, memories, symbols or remarkable facts. It was not until the Republic, the time of the First Triumvirate (Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus), that we find the first portrait of the three –still alive back then– shown in one of the coin’s front, with the representations of historical scenes and facts of Rome. An example is the silver denarius of Titus Carisius –from 46 BC–, which shows the head of Juno Moneta in the obverse, divinity charged with watching over the financial resources of the state, and a laurel wreath, some nippers, an anvil, a die and a hammer in the reverse, some indispensable tools in order to coin.

In the second bloc, which presents numismatics from the death of Julius Caesar to the access of Augustus to the Empire’s power, coins reflect “the situation of uncertainty and convulsion that predominated in the Roman world until Augustus succeeded in taking control”, as Tarrats explains. This is the beginning of a period on which coins become a kind of propaganda, their images tell us about the conquest of new territories. We find, from this period, a silver denarius of Marcus Antonius, which shows a praetorian galley in the obverse, and a legionary eagle between two military insignia in the reverse. The exhibition mentions the fact that this coin was mint by Marcus Antonius during the preparations of the battle of Actium. On the obverse they indicated his position of triumvir and, on the reverse, the number of legions he had at his disposal, in order to flaunt this power and boost the morale of his troops. However, propaganda was not enough; Marcus Antonius lost this battle and would end up killing himself, while Augustus eased the way towards his Empire.

In the third bloc, the image of the Emperor becomes an essential iconic element. The emperor is no longer the only one that can allow magistrates to produce coins, whether they are made of silver, aurichalcum (brass) or bronze. As for the low number of current coins of the period, they were only made by imperial mints, in Rome and in Hispania, under the control of Augustus. From this period, we’ve selected a coin that refers to a historical event: the Caesaris astrum (Caesar’s comet) was observed in Italy for seven days, in July 44 BC, the year Julius Caesar was murdered. This phenomenon was interpreted as a sign of his deification –“Caesar’s soul”–, becoming a powerful symbol of political propaganda that boosted Augustus. This comet was meant to disintegrate, as it was no periodic. Despite some scholar have identified it as the Halley, this is a wrong fact because the comet, which has an orbit of an average 76 years, went past the earth in the year 86 BC and then, in 11 AD. Also from this period, we find the golden coins, an aureus of Tiberius, which shows the laureate head of Tiberius in the obverse and, in the reverse, the laureate head of Augustus.

And so, we make it to the last area, which talks about Tarraco’s mint, one of the most important ones when I comes to coin production of the Roman Hispania in the Republic period. The coins minted in Tarraco during this period covered all the usual values (sestertii, dupondi, ases, semis and quadrantes), and the showing gathers all the coins made in the period of Augustus and Tiberius. From this time, we find a coin with the radiate head of Augustus in the obverse and an altar with palm in the reverse.

Finally, the exhibition also provides the so-called “Family Tree of Power”, with the greatest families. It also provides information about the current coins, their value, and the salaries of the different classes of the Roman society: politics, doctors, civil servants, famous artists… Equivalences that come to prove that despite coins changing, compensations don’t, a part from very honest exceptions of course.

INFORMATION:

Location: Museu Arqueològic de Tarragona (plaça del Rei, 5)

Schedule: 12pm. Duration, 1h aprox.

Price: included in the museum ticket.

Guided tours: 20 Marh, 17 April, 15 May and 19 June, 2016

More information and bookings: +34 977 25 15 15 / +34 977 23 62 09 / mnat@gencat.cat

Text: Ivan Rodon i Tenas (@irodon on Twitter)

Pictures: Pere Toda (@ptodaserra on Instagram)

Translation: Artur Santos (@ArturVilaniu on Twitter)